-

-

-

Moldover

- 22 March, 2011 in People & Adventures

The Controllerist Manifesto

Moldover’s Octamasher as a Modern Participatory Musical Instrument:

Technology As Keeper of the Groove, Artist as Designer of the Experience

“This article, from 2010, summarizes the implications of Controllerism on modern music, society, and the market, from a musicological and technological standpoint. Author John Clements analyzes Moldover’s Octamasher as an example of how CONTROL over our sounds and our experience with them can be a social participatory experience rather than an exclusively commercial, presentational model for musicking. Following the relatively short history of recorded and reproduced music and the advent of digital technology, Clements asserts that Controllerism is a logical return to the roots of music-making, where the artist (as ‘Shaman’, thanks Brian Eno) curates the experience of those who participate actively in the process of selecting, performing, and responding to the art. By repurposing these technologies and concepts, taking them back from the recording industrial complex, Controllerists are essentially encouraging their musical community to rebuild ‘what it is to make and partake in music’.” -copyright John Clements, 2011

“What people are going to be selling more of in the future is not pieces of music, but systems by which people can customize listening experiences for themselves. Change some of the parameters and see what you get. So, in that sense, musicians would be offering unfinished pieces of music – pieces of raw material, but highly evolved raw material, that has a strong flavor to it already. I can also feel something evolving on the cusp between “music,” “game,” and “demonstration” – I imagine a musical experience equivalent to watching John Conway’s computer game of Life or playing SimEarth, for example, in which you are at once thrilled by the patterns and the knowledge of how they are made and the metaphorical resonances of such a system. Such an experience falls in a nice new place – between art and science and playing. This is where I expect artists to be working more and more in the future.â€

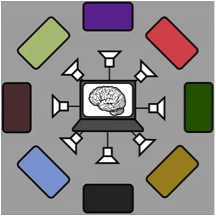

-Brian Eno, 1995 interview with Wired MagazineIn 2006, inspired by the interactive future-art festival Burning Man and his perceived need for interactive music there 2, musician Matt Moldover created the Octamasher, a multi-player instrument which perhaps embodies exactly the type of system that Brian Eno is talking about. In a video from one of the many festivals and events where people are using the instrument, we see what appears to be a ‘digital drum circle’ of sorts.  8 people are facing each other, around an octagonal structure, each with a surface in front of them, including piano keys, buttons, knobs, and joy-wheels. The people are all bobbing their heads in relative sync, smiling, looking at each other, mashing keys and twisting knobs. The music emanating from the speakers in front of each player is a mixture of the oft-sampled “Scorpio†by Dennis Coffey, a cowbell playing Afro-Cuban clave, the theme from American 70’s TV show “Sanford and Sonâ€, funk icon James Brown shouting “Get on up,†and turntable scratch sounds, among 3 other sources of controlled sonic collage. The players are acknowledging each other’s actions positively, and learning together, and the sounds are in sync, layered and mixed, with accents according to players’ manipulations and mutual inspirations.

Moldover’s Octamasher, through artistically designed appropriation of control over some of the sonically iconic production and performance methods of reified, commercially formatted music, and offering the use of this control in a networked, synchronized performance framework, is a return to the pre-industrial roots of musical practice, the participatory, the fun, and answers the need of humans to play and create shared mental spaces in which to do so. The Octamasher is a participatory model for the conversion of control, one that does not just free the mind from the presentational models of recording industry products and Live Nation concerts, but also the body. It harnesses the dance (either mental or physical) that we perform in response listening to recordings of music, allowing us to mediate it further by technology into a feedback loop, or a simulacrum of playing an instrument, hearing its tones, and adjusting one’s haptic timing to control the continuum of sound.

Since the development of audio recording and playback technology, musical artists have appropriated sonic control via co-option of the devices and techniques necessary to facilitate the playback of recorded sound. Originally applied by the commercial entertainment establishment for the purpose of selling recordings of songs as products, the recordings, playback devices, and now the tools used in production of studio audio art have now been redefined as musical instruments themselves, mediated by developments in technology.

The trend began with the turntable, radio, and John Cage’s 1939, first-known performance piece for turntables as instrument, “Imaginary landscape #1â€, that used test-tone calibration records played on variable-speed turntables, along with radios tuned to random stations (Miller 15, 98, 255). From the 1970’s onward, hip hop and club music DJs used vinyl records and turntables as instruments, quickly appropriating from the music studios devices like volume mixers, equalizers, delay units, compressors, tape decks, drum machines, and other effects.  During the past 3 years, the music instrument market has seen a rapid increase in the number of musical products that mediate control. Many of these surfaces for controlling sound in real time do not index musical instruments and our physical methods of playing them, as the MIDI pianos, drum pads, guitar midi pickups, and CD-turntables of the 1980-90s did.

The progression of controller products released since then has gone from surfaces of just knobs, buttons, and faders to time-coded vinyl control of digital audio, jog-wheels, joysticks, and arcade buttons, grids with LED lights under them and multi-touch feed-back screens. Software communicates with the hardware and offers configurable parameters for almost any aspect of timbre, pitch, time, and modulations between all of them. Studio-created electronic effects are modeled in real-time, and the use of these effects has become an instrument in its own way, rather than part of the instrument. As a solo musical performer, in his presentational mode, Moldover plays his hand-made controller interface, a mixture of arcade buttons, sliders, knobs, toggle switches, and capacitive touch-strips, even at one point a giant trackball that is immediately recognizable as the one in the “Golden Tee†golf bar-arcade game. He also plays guitar, adding an established performance element to his hands-on electronic ‘Controllerism’.

The ideal example of modern production technology aiding and abetting this re-appropriation and redefinition of control over commercially reified music is Moldover’s group-musicking instrument, the Octamasher. The device is designed so that a group of people can all generate and control aspects of a seemingly endless, constantly changing piece of music. The synchrony is maintained by an “electronic musical brainâ€, to which 8 control stations are linked. The brain supplies the material, and mediates the control. The people, through participation in its supplied grooving models, become one, making music that is derived from a common pop-cultural pool of audio samples, loops and snippets of material from songs, video games, movies. The music and sounds are at once knowable and new, referencing familiar songs and sounds from our commercial entertainment culture (James Brown, R2-D2), but prepared by premeditated artistic design to be reassembled, filtered, chopped and altered by the hands of the performer-audience.

Participatory music, according to Thomas Turino’s theories laid forth in his 2008 book Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation, should include a variety of roles, and room for non-uniformity, so that people will not get bored. The Octamasher provides 8 distinct roles, and enough variety of sound and control, that people if bored with the first station they sit at, they will try others until they find the one that suits their preferred role in the music.

Turino’s definition of participatory musical practice also dictates that it generally must include, or provide roles for people with a wide range of abilities. The Octamasher has inviting, approachable interfaces that people are most familiar with, and ubiquitous as a musical instrument, the piano keyboard, and the wheels and functions are clearly labeled and coded with bright colors according to their functions. The synchronized nature of the sounds and loops means that nobody who misses the timing is going to “train-wreck†the mix of sounds; elements come in on time, and at relatively balanced level relationships, so nobody stands out too much sonically. At the same time, an uninitiated player can walk up and find a sonically pleasing combination of keys and knob/fader/wheel motions relatively quickly, and feel really cool doing it.

Another hallmark of participatory musical traditions that Turino identifies is a level of difficulty or complexity with an upwardly expansive boundary. The Octamasher provides a challenge of scale for the group playing it, in that the number of people playing increases the density and activity of the sounds played, creating the potential to make lots of noise. When players are focused, thoughtful, and have taken the time to learn the range and roles of their controls, they can then begin to form cohesive musical patterns together by giving each other sonic space to assume core and elaborative roles in defining the sound being made. This is obvious in a video of the Red Bull Beat Riders playing the Octamasher, where the group are jamming together, and one player positively singles out the sonic result of another’s actions, saying “â€. At the rhythm station, he then proceeds to add his own control improvisations, timing and spacing his moves with the other parts.

The amount of culturally shared sampled sound material available in the Octamasher’s memory provides a learnable catalog of sounds with which people can gain more and more familiarity, and each sound has multiple possible configurations for controlling rhythm, pitch, and timbre. The potential for synchrony and the collaborative nature of the instrument for generating cohesive ‘songs’ from the phrases and sounds provides a challenge that brings all members of the group together. The challenge of finding the right combination of sound and timing, getting into the groove and adding to it, is similar to the challenge of a good blues jam, or drum circle.

Turino also mentions core and elaboration musical roles in relation to how dependent the cohesion of participatory music is upon these activities (Turino 31). The carefully sampled nature of the Octamasher’s sounds evens the relationship between these types of roles (rhythm section vs. lead vs. dancers), opening up the shared responsibility for the groove into a feeling of free play, since the ‘musical brain’ in the computer is maintaining the core roles of keeping time and balancing/mixing the sound levels together in a way that leaves space for improvisation but always has a constant structure, looping the rhythm section and bass lines.

The structural characteristics of participatory music that Turino outlines, feathered beginnings and endings, open-ended structure, and sonic density which masks individual inputs to varying degrees, are all present in the looped, dynamically auto-mixed, down-beat synchronized aspects of the Octamasher.  In addition, Turino’s “security in constancy†(Turino 88) participatory principle that he ascribes to electronic dance music is reinforced by the use of looping, synchronization, and the tempo/key mapping work done by Moldover.

The question must be asked of this technology-mediated participatory framework: What types of relationships are being defined here between the players, between the players and the sounds, and between the sounds themselves? To understand the relationships, it is necessary to organize and analyze the controllers according to their relationships to core participatory roles and elaboration roles defined by the various keys, knobs and sounds.

The Octamasher’s ‘Drums’ controller’s white keys play drum loops that come in on the downbeat, and the black keys play one-shot samples. Wheels above the keyboard allow the player to time-stretch, alter the pattern, reverse the loop, or adjust the master tempo. The presence of master tempo control places the ‘drums’ controller as most closely related to the core role of keeping tempo in participatory music-making. The ‘Mash up’ controller also fills a fairly core participatory role, as relates to the density and variety of sonic material generated as a whole by the Octamasher, since it plays full-frequency, highly recognizable songs like “Tequila†by the Champs. Songs start playing on the next downbeat. The red keys offer 1 “palette†of songs, and the blue keys on the right offer a second range of music, to be cross-faded DJ-style by a knob in the middle and some frequency-blending wheels that blend highs of one song with the lows of another.

The ‘Remix’ controller plays longer sections of songs. It allows its player to turn vocals on and off, to bend the pitch, to ‘chop’ the song with rhythmic sections of silence, and to cut out high frequency or low frequency. This controller, like the ‘Mash up’ controller, offers sonically dense and potentially structurally complete song material, and its player has wide control over the aspects of its density and timbre. The ‘Percussion’ controller also has the aspects of down-beat looping and of consistency in playback, and though the sounds are not as complete and dense as the other controllers that are in core roles, in offering controls over swing, it offers the player to alter the groove of the entire output in ways that others certainly cannot.

On the “Bass Lines†controller, each group of colored keys plays a sliced up bass line, with each key triggering playback of one slice. The controls available here are: pitch bend, auto funk, ring mod, and buttons to change banks of bass lines. This controller does not loop bass lines, but requires perpetual input to make sound.  Holding down the bass line keys repeats the notes in time with the music, and the lines are chopped into simple groupings, making the instrument suited to bass-player types who want to take a potentially more active, elaborative role that is also at times a more static support role in the bottom end of the sound.

The ‘Riffs’ controller plays recognizable riffs: keyboards, sax, guitar, and such. These instruments have more of a ‘lead/solo’ role, but can also function as ornamental when there is greater density in the sound. The knob controls offer similar effects to a guitarist’s rig: echo, distortion, and reverb, all which sonically alter the focus of the sound to make it blend in more, either rhythmically, timbrally, or spatially. The ‘Vocals’ controller offers different vocal samples played on each key, upward and downward pitch bend, reverse playback, echo, and ‘slicer’ effects. Similarly to the ‘Riffs’ controller, this controller can assume more forward roles in the musical mix or be altered to blend or morph the vocal, which in most pop mixes is the most front-and-forward. The ‘Scratch’ controller, also in an elaborative role, mimics the scratching of turntables by playing modulated sounds of ‘scratch samples’. These are hits and one-offs that are directly mimetic of turntable performance techniques, with a tone control, and two timbre/rhythmic effects.

All of the music found in the Octamasher, by Moldover’s admission, is sampled from his own collection, which has been edited to grab a vocal, bass line, riff, chord progression, drumbeat, or entire section/phrase 2.   While it reflects Moldover’s personal taste in music, it is quite a diverse range of music [see Appendix A], including classic rock, funk, jazz, metal, soul, video game music, hip hop, classical, r&b, and some left-field choices like Frank Zappa, Aphex Twin, and Trevor Wishart. Much of the funk, rock, and soul music in the Octamasher has found its way into popular culture as samples we recognize from rap music and electronic music, and samples like the voice of James Brown or the Winstons’ “Amen Brother†break instantly conjure to today’s listener the music of television, movies, games, and advertisements, as well as in nightclubs and places where people come together to groove. The samples and one-shot sounds are all recognizable- from movies, TV, and other pop-culture sources, from R2D2 of Star Wars to John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address and ‘Scorpion’ from the Mortal Combat video game series. Aside from being sounds and songs that Moldover things are cool, these are sounds that represent a wide spectrum of culture in America.

Beyond the functional design and editing choices for the music and samples, the Octamasher is an extension of Moldover as an artist, a selector of content from our shared cultural archive. This fits with Brian Eno’s insightful assignment of the DJ/Electronic musician as curator of archived culture. In his 1995 interview with Wired Magazine, Eno says “An artist is now a curator. An artist is now much more seen as a connector of things, a person who scans the enormous field of possible places for artistic attention, and says, ‘What I am going to do is draw your attention to this sequence of things’â€.

In our interview, I asked Moldover how the people at festivals behave when they play the Octamasher. They “teach each other how to play it, and figure out as a group how to play it together… the people who are familiar with interactive art get it right away, they are like ‘Oh, this is fun!’  Moldover also admits that he has had to “curate it… and get people into that mindset of playfulnessâ€. According to Mr. Moldover, “about half the people get it, saying ‘Oh, it’s like a drum circle where we jam together’…Half the people look at it, and are like, ‘why would I do that?’â€Â The ideal venue for the Octamasher, according to Moldover, is the Burning Man festival, but potential looms not just at festivals but in schools, installations, and group concert performances. New controllers and music can be added in variant forms according to musical styles/tastes, and alternate types of control interfaces like drum pads, touch-screens, microphone inputs, instrument inputs and more. As the design is modular, and likely networkable, the Octamasher concept could be scalable into larger configurations, or send/receive audio via internet to create global virtual drum circles.

Though the Octamasher is a participatory model, as Moldover put it in our interview, “the instrument designer is still in the artâ€. The integrity of the Octamasher’s authorship, even though the performers are not the composers, is preserved in a distinctly different way than that of an instrument-builder or composer, a drum-circle leader or a keeper of folk song traditions. The “musical brain†and its software, where limits and nature of controls are defined, sounds are chosen, and where the relationships and interactivity of the players’ inputs are delineated, are the controls now, rather than the ego of an individual. The composer-designer-individual Moldover is still present in the art, as the programmer, selector, definer, provider of control and of what is being controlled.

In this sense, Moldover’s Octamasher can be seen as a meta-controller-instrument, 8 parallel systems ultimately in sync yet with built-in ways for its players to control various participatory discrepancies and increase or decrease the density of the sound.  It is an instrument designed by an artist to provide control over a curated library of sound, a cultural archive from which most will recognize material they enjoy listening to and discover new dimension in mashing it up with the other sounds present.

For the participant, the sense of immediate control mediated by technology, and the results of voluntary, low-pressure collaboration with others, results in a sense of fun, playing, celebrating our shared sounds and the cool ways we can use technology to mix, alter, and in essence, put our artistic touch on the sounds in the same way a DMC champion DJ like Craze, a techno mixer like Richie Hawtin, or a top-notch electronic producer/performer like Squarepusher could. The controls and the descriptions provided for using them are mimetic of the types of sonic control that have developed as results of DJ culture and electronic studio audio art production.

The manner of control given to the players of the Octamasher represents a new vocabulary of sounds that index or are metaphors for modern “media-technology-as-instrument†gestures and effects. Just as when we hear an acoustic guitar, in our mind, we picture the instrument being played, the electric/mechanical/acoustic manipulations of turntablists such as the X-ecutioners and InVisiBL SKratch PiKLZ and electronic music producers like Aphex Twin or Amon Tobin act as indexes of new performance and production techniques that fascinate modern listeners. In a way, these performers created new culturally shared sonic “artifacts†which we recognize as the sounds of media being manipulated. The quick-cut, scratch, filter-sweep, cross-fade, stutter, cue drop, and various audio effects such as ring modulation made available by the Octamasher can be seen as metaphors for the complex techniques of sonic control that do not exist in the real acoustic world.

Examined via the taxonomy of timbre perception in electronic music that Cornelia Fales laid forth in her article “Short Circuiting Perceptual Systems: Timbre in Ambient and Techno Musicâ€, the source characteristics in the sounds contained within and created by the Octamasher serve to contextualize them as being non-acoustic and originating in the virtual realm of technology being wielded musically.  Fales theorizes that the sounds found in electronic music fall into categories that either index real sound and their sources, suggest acoustic nature, or do neither. These imaginary sounds form in our brains a sort of “Rubin’s Goblet” (the faces/vase negative space-positive space illusion) effect, where we fill in meaning and create “artifactual†definitions for sounds we hear as a response to these sounds being ungrounded in acoustic reality (Greene 168). Fales suggests that we assign unique meaning and context to these “artifactualized†sounds, since they do not follow acoustic rules of the natural world.

R. Murray Schaeffer’s term “schizophonia” refers to the split in meaning that occurs when a sound is electro-acoustically stored and reproduced, the separation in our mind of the sound from the meaning of its real-world index.  Fales posits that in electronic music, schizophonia allows for the creation of shared conceptual realms, which are based upon projected or shared meanings for the sounds and their timbral combinations (Greene 175-6). The Octamasher is also interesting in light of Stephen Feld’s concept of “schizmogenesis”, which refers to the recombination and re-contextualization of sounds that have been separated from their indexed sources via electro-acoustic means (Greene 75).  Some of the songs sampled for the content of the Octamasher contain samples themselves; in fact, the entire process is essentially “schizmogenicâ€. The parts of songs and mass-mediated culture themselves are being recombined and re-contextualized in real-time, according to who is playing them and how they are combining them.

The core concept being projected by the Octamasher, that everyone can, through the mediation of technology, find common musical ground to play on, is indeed utopian, egalitarian, but definitely true. Quantization and the application of “groove templates†to loops and performance input has made this possible, as have increasingly powerful software which analyzes beats per minute, key, time signature, and can even near-automatically beat-map and pitch-match songs into a mash-up. Even some basic functions of the DJ/engineer, like equalization and volume balance are now relegated to plug-ins and software, as Moldover’s video demonstrating his “smart mixer†shows 6. Using technology to accomplish  in real-time, the more functional and mundane musical tasks of providing clarity, balance, and synchrony allows the performers/players of the Octamasher to focus on deeper levels of integration and response to the sounds and each other.

The response of the music to tactile input and the response of the other participants to this input’s effects on the musical sounds create a powerful iconic projection of our modern belief that technology gives us unprecedented control. Many of us carry powerful supercomputers in our pockets that store and provide information, entertainment, images, and other collective and individual ideas. Products and websites that make us feel smarter, more talented, and more connected abound. As of the writing of this paper, the top-selling Apple Ipad music application is “djayâ€, which allows you to mix 2 pieces of digital music via an interface that imitates two records on turntables, with controllers for mixing, tempo, and pitch. The software mediates the selection process by automatically detecting beats per minute and matching, as well as featuring an automatic mix mode with fade, backspin, reverse, features which emulate the sound of DJ vinyl manipulation. In a 2002 article on electronic dance music for Leonardo Music Journal, Ben Neill’s prophecy that the “laptop is replacing the acoustic guitar as a primary instrument of expression for scores of new musicians†(Neill 3) has been fulfilled. Now, more than ever, the connectivity of these new computers-turned-instruments, and their relationship to the total experience, including lighting and video manipulation, is defining the way we create and consume music socially.

At this point, ‘Controllerism’ stands at the forefront of technological mediation of performance and composition, and I think that the Octamasher represents one of the earliest-realized (of many to come) participatory musical applications of the Digital Age philosophy of technology as a means for mediating ideas, communication, and as not just an extension of our person, but our community.

Using one “brain” to link together the creative expression of 8 humans, the Octamasher seems to offer a utopian view on where the creation of music using digital means can take society; audience and performer are one and the same, and through controlling timbre and rhythm, playing together with a shared language of audio samples and loops, people can participate in creating something together that is new but comfortably recognizable. In the Octamasher’s framework for musical participation, the mediation by technology of control over the timbre, rhythm, directionality, combination, and other aspects of imagined or reorganized sounds creates an opportunity for people to feel they have more control over their experience, over the sounds that create and represent shared feelings, values, and experience for those participating in music.

The participatory field defined by Thomas Turino, as he applies it to electronic music, results in his conclusion that the musical content indexes studio audio art but uses the aspect of repetition, “security in constancy”, to create a groove and sense of motion to the music which fosters participation, dance, and gives the sense that the ‘groovers’ are as much a part of the music making as the ‘groov-ees’ (Turino 88).

The Octamasher seems to offer the perfect model for shared participation and performance, while still allowing the artist/engineer/designer a place of overall control and originality/authenticity in the brain of the device and the selection of audio content for the various modules. It may be that Moldover’s networked ‘meta-instrument’ (Miller 288) and its mediation of control is on the forefront of  “a larger cultural change, something that the late writer Terrance McKenna described as the Archaic Revival [the return to a perspective on self and ego that places them within the larger context of planetary life and evolution; the re-empowerment of ritual and the rediscovery of shamanism through technology and connectivity]. McKenna suggested that through the emerging electronic media and connectivity art would assume a role similar to its position in preliterate societies†(Neill 5-6).

In Matt Moldover’s words, the Octamasher “brings back the group experience and the communication, the social aspects of music that get lost in a lot of electronic musicâ€.  The experience offered by the Octamasher, with its groove-synced, carefully curated audio samples and loops, and the various balances of control it gives players over a shared collection of fragments from our digital audio culture, certainly assumes the participatory musical role of defining a space for our spirits to play and celebrate our cultural assets and offers the artist, Moldover, the role of the shaman, the designer of the experience.

Bibliography:

Eno, Brian. “Gossip is Philosphy†Interview with Kevin Kelly for Wired Magazine, May 1995.

Fales, Cornelia. “Short-Circuiting Perceptual Systems: Timbre in Ambient and Techno Musicâ€,

From Green, Paul, and Thomas Porcello, ed. Wired For Sound: Engineering and Technologies

in Sonic Cultures, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, 2005.

Iyer, Vijay. “On Improvisationâ€, from

Miller, Paul D., ed. Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2008.

Moehn, Fredrick J. “The Disc is Not the Avenue: Schismogenetic Mimesis in Samba Recordingâ€, from

Green, Paul, and Thomas Porcello, ed. Wired For Sound: Engineering and Technologies

in Sonic Cultures, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, 2005.

Neill, Ben. “Pleasure Beats: Rhythm and the Aesthetics of Current Electronic Musicâ€

Leonardo Music Journal, vol. 12, Pleasure (2002), pp. 3-6. Pub. MIT Press.

Reynolds, Simon. Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture,

Little, Brown, and Company, Boston, 1998.

Turino, Thomas. Music As Social Life:The Politics of Particpation, Chicago University

Press, Chicago and London, 2008.

Materials collected: (cited in text with superscript)

1. Moldover, Matt. Written responses and comments on the Octamasher, Dec. 2010.

2. Moldover, Matt. Audio recording of phone interview by John Clements, Dec 2010.

3. Moldover, Matt. List of songs sampled by Octamasher, Dec 2010Â (See appendix A).

4. Moldover, Matt. Image of Octamasher, 2006.

Videos referenced:

5. Red Bull BeatRiders Octamasher Session, Aug. 2007: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AM9Hxwa6fiI

6. Moldover’s Approach to Controllerism (part 2) video – cue time: 3:41 “The Smart Mixerâ€

7. Moldover‘s Octamasher, Dec. 2006: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f6VJ6RXroNE

APPENDIX A:

MOLDOVER’S 8MASHER MUSIC LIST:

Tool: (-) ions,

A.D.O.R. – One for the Trouble,

Korn: Blind,

Beck: Loser, (Express Yourself),

Led Zeppelin: When the Levee Breaks,    rock – drums

Marvin Gaye – Let’s Get it On,    soul

Jon Mayer: Neon, (Cissy Strut),        funk

Charles Wright – Express Yourself,     soul

Temple of The Dog: Pushin’ Forward Back,

Tool: Reflection,

Tool: Intolerance,

The Beach Boys – And Your Dreams Come True,

The Meters – Cissy Strut, funk

Phish: Cavern, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â hippy jam band 90s

Tool: Prison Sex,

Rodgers and Hammerstein – My Favorite Things,  classic

Monty Python’s Quest for the Holy Grail,  SAMPLE movie

The Doors: Break On Through, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â classic rock

Pink Floyd – Comfortably Numb,

Edgar Allen Poe: The Raven, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â SAMPLE Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â classic culture

Soundgarden: Rusty Cage, (So Whatcha Want),

Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers – Mary Janes Last Dance,

The Beatles: Sgt. Pepper’s Reprise, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â hippies

Beastie Boys – So Whatcha Want, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 90s rap, *sampled zeppelin

Pink Floyd: Time, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â psychedelic acid rock

John Coltrane: Blue Train,                                 jazz, well known

Funkadelic: Maggot Brain, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â psychedelic funk

(For What it’s Worth),

The Honey Drippers: Impeach the President,

Janis Joplin – Mercedes Benz,           vocal

AC-DC – Back in Black,                                             rock – chords/riff

Pink Floyd: Money,                                                        psychedelic rock,  bassline/sample

Trevor Wishart: Vox 5, (I Wish), Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â electronic-obscure

Black Sheep – The Choice is Yours, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â hip hop

Beck: Loser,

Edgar Winter – Frankenstein,

Herbie Hancock: Bubbles,

Kool & the Gang: Jungle Boogie, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â funk

Clerks: Berserker,                                                        SAMPLE from movie

Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Give it Away,

Tori Amos: Caught a Little Groove, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â pop

Bjork: Human Behavior, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â electronic

Steve Miller Band – Fly Like an Eagle,

Aphex Twin: Selected Ambient Works Vol. 2-Disc 2-Track 4,

Herbie Hancock and the Headhunters: Chameleon,   funk

Waking Life: Things are Just Starting,

Pearl Jam: Once, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â rock, 90s

Lou Reed – Walk on the Wild Side, (Frankenstein),

Frank Zappa: Broken Hearts are for Assholes,               freak rock

Alvin Lucier: I am Sitting in a Room,

Jurassic 5 – The Influence, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â hip hop

Slick Rick & Doug E. Fresh: La Di Da Di, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â hip hop

Lionel Richie – Brick House, Motown,

The Crystal Method: Busy Child, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â electronic rave culture

Pearl Jam: Jeremy, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â rock, 90s

Tool: Useful Idiot, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â rock, 90s

The Matrix: Rules, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â well known movie SAMPLE

Buffalo Springfield – For What it’s Worth,

Michael Jackson: Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 80s iconic

Jimi Hendrix – Hey Joe, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â blues, hippy/psychedelic

The Beatles: Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown),

Star Wars: The Darkside, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â SAMPLEÂ Â movie

The Who: Baba O’Riley,

Arrested Development – Tennessee, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â hip hop, old school

Temple of the Dog: Wooden Jesus,

The Champs – Tequila,

Eminem – Without Me,

Extreme: More Than Words, Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â ****

Nirvana – Smells Like Teen Spirit,

System of a Down: Sugar,

Sneaker Pimps: 6 Underground,

Van Halen: Top Jimmy,

Geggy Tah: Aliens Somewhere,

Eurhythmics – Sweet Dreams, 26

The Chemical Brothers – Block Rockin Beats,

Primus: Tommy the Cat,

Michael Jackson: Billie Jean,

Bangles: Walk Like an Egyptian,

JFK: Power,                                                                  historical SAMPLE

JS Bach – Cello Suite No. 1, 28Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â classical

The Police – I’ll Be Watching You,

Radio Head: High and Dry,

Alanis Morissette: One Hand in My Pocket,

Sean Paul (Featuring Rahzel): Top of the Game,

Steppen Wolf: Magic Carpet Ride,

Alice in Chains: Would,

Queen – Another One Bites the Dust,                           rock, chords

Jamiroquai:Â Bonus Track 2,

Squarepusher – Fat Controller,

Earth Wind & Fire: Shining Star,

Jan Hammer: Miami Vice Theme,

King Crimson: Elephant Talk,

Eric Schwartz: Dirty Laundry List,

Peter Gabriel and Nasrat Fateh Ali Khan: Taboo,

Rage Against The Machine – Know Your Enemy,

Stevie Wonder – I Wish,

The Beatles: Strawberry Fields Forever,

Led Zeppelin: Black Dog,

Michael Jackson: Beat It,

Herbie Hancock: Hang Up Your Hang Ups,

Prodigy – Smack My Bitch Up,

Peter Gabriel – Big Time,

DJ Shadow: What Does Your Soul Look Like, (Workin’ Day and Night),

Primus: Jerry Was a Racecar Driver,

Michael Jackson (featuring Vincent Price): Thriller,

American Psycho: Breakdown,

Steely Dan: Do It Again,

Tool: Forty Six & 2,

Public Enemy – Bring the Noise,

The Greyboy Allstars: Tenor Man,

Monty Python’s Quest for the Holy Grail: Monks’ Chant            SAMPLE

Michael Jackson – Workin’ Day and Night,

Beck: Where It’s At,

U2: Mysterious Ways,

Bela Fleck & The Flecktones (feat. Victor Wooten)- Sinister Minister,

Jeff Buckley – Young Lovers,

OutKast – BOB,

Queen: We Will Rock You,

Ah Ha – Take On Me,

Nirvana: Lounge Act, Brand X: Born Ugly,

System of a Down – Know,

Mortal Kombat: Get Over Here,                                             SAMPLE

Aphex Twin – Bucephalus Bouncing Ball,

Magnolia: Who I am,

Amon Tobin: Reanimator,

Tool: Prison Sex,

Portishead: Over,

Danny Elfman – The Simpsons Theme, Puppies & Babbies,

Funkadelic – Gan You Get to That, and more…

-